The Long-Lost 'Kenyon House'

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The Story History may repeat itself, but the documents that crystallize a historical moment do not. Sound recordings, maps, daguerreotypes, photographs, films, fragile books, obscure play scripts: these and millions more national treasures held in the collections of the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress were suffering from two maladies: the ravages of time, and obscurity. But no longer.

History may repeat itself, but the documents that crystallize a historical moment do not. Sound recordings, maps, daguerreotypes, photographs, films, fragile books, obscure play scripts: these and millions more national treasures held in the collections of the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress were suffering from two maladies: the ravages of time, and obscurity. But no longer.

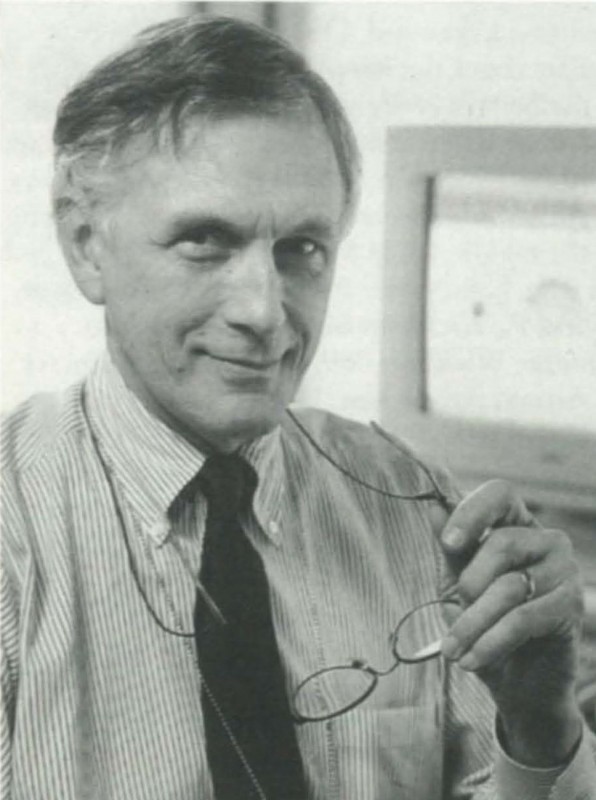

Thanks to the ambitious American Memory project, coordinated by Carl Fleischhauer '62, anyone with access to the World Wide Web can call up memory.loc.gov/ammem and enter a virtual museum, where some million remarkable documents, in a wide range of media, reveal themselves at the click of a mouse.

While the center was established by the U.S. Congress in 1976 to record the traditional expressive culture of the United States, the American Memory project was undertaken to preserve and disseminate those "documents" by digitizing and putting them on the web.

Fleischhauer's attraction to collaborative projects that combine artistic content with technology has shaped the trajectory of his career so far, as has his desire to serve the public. After a year in India on a Fulbright grant and a two-year stint in the Army, the honors philosophy graduate earned an M.F.A. in photography from Ohio University in 1969.

As a graduate student, his film entitled "John Mitchel Hickman," a cinematic portrait of a young bluegrass banjo player in Columbus, Ohio, tied for second place in the Fourth National Student Film Festival at Lincoln Center in New York City. This award led to six years of television and film production at a West Virginia public-television station.

In 1976, Fleischhauer joined the Library of Congress, where he has been employed ever since, initially as a folklife specialist in ethnographic media documentation at the Library's American Folklife Center. In 1990, he began working on the digital collection for American Memory, shifting his focus from the production of documents to the preservation of them in publicly accessible form.

Among the million documents he has helped expose to ever-widening audiences are some that he himself produced for the American Folklife Center in the late 1970s while participating in a field-study project on the Buckaroo culture of northern Nevada. In the 1980s, the photography, film footage, interviews, and written text that were his contributions to the field-study project became available to a wider audience on a laser videodisc Fleischhauer produced himself. The laser disk, which includes an interactive program used in the Folklife Center's 1983 exhibition on the image of the cowboy in American culture, could be purchased from the Library of Congress, although that technology has now been superseded by the DVD. (Fleischhauer's article on this laser disk was published in the Summer 1983 edition of the Bulletin, Volume 7, Number 3.) Now, as a result of digitizing, those same documents appear as a collection on American Memory, accessible to an incalculably larger audience curious about Buckaroo culture.

Fleischhauer also appears in library catalogs as coauthor of Blue Ridge Harvest (1981), The Grouse Creek Cultural Survey: Integrating Folklife and Historic Preservation Field Research (1988), and Documenting America, 1935-1943 (1988). Forthcoming next year is his latest book, Bluegrass Odyssey: A Documentary in Pictures and Words, 1968-1981. In addition, he has coproduced an audio compact disk called The Hammons Family: Traditional Music and Narratives from a West Virginia Family (1999).

His role as a conservator of cultural knowledge (a title Fleischhauer makes no claim to himself) is reflected in his latest assignment at the Library of Congress, where he is creating a digital repository for recorded sound and moving images collections. These will be preserved in the new National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia, which is scheduled to open in 2003.

Devotion to the cause of conservation under-lies many of Fleischhauer's civic activities, as well. In the small Chesapeake Bay community in Calvert County, Maryland, where he lives with his wife, Paula Johnson, he has served recently on the boards of an archeological museum, the county historical society, and a local land trust that manages more than two thousand acres of woods and wetlands on the bay.

Fleischhauer's work confirms his belief in the kind of liberal-arts education Kenyon offers. "At the Library of Congress," he observes, "we confront an interesting and varied array of problems. We're never quite narrowly academic or narrowly technical. Because we deal with a range of things, creative thinking is repaid handsomely. A liberal-arts education gives us a place to start."

Belief in the College has led Fleischhauer to sponsor numerous externships for Kenyon students over the years. Most recently, he hosted Elizabeth Erickson '02 at the Library of Congress for a week during winter break.

Working in large organizations has taught Fleischauer that one of the crucial skills in life is "the ability to persuade people that a certain course of action would be wise. The ability to persuade depends on language, being able to write or speak in ways that are convincing. Colleges like Kenyon offer an opportunity to learn to state your ideas more clearly."

Peter Dickson '69 explores the history of Mount Vernon's first brick hotel.

Read The StoryA look at the Kenyon campus and how it grew.

Read The StoryPresident Robert A. Oden Jr. reflects on Kenyon history in honor of the College's 175th anniversary.

Read The StorySir Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, Lord Kenyon and Sixth Baron of Gredington, delivers the 1999 Founder's Day address.

Read The Story